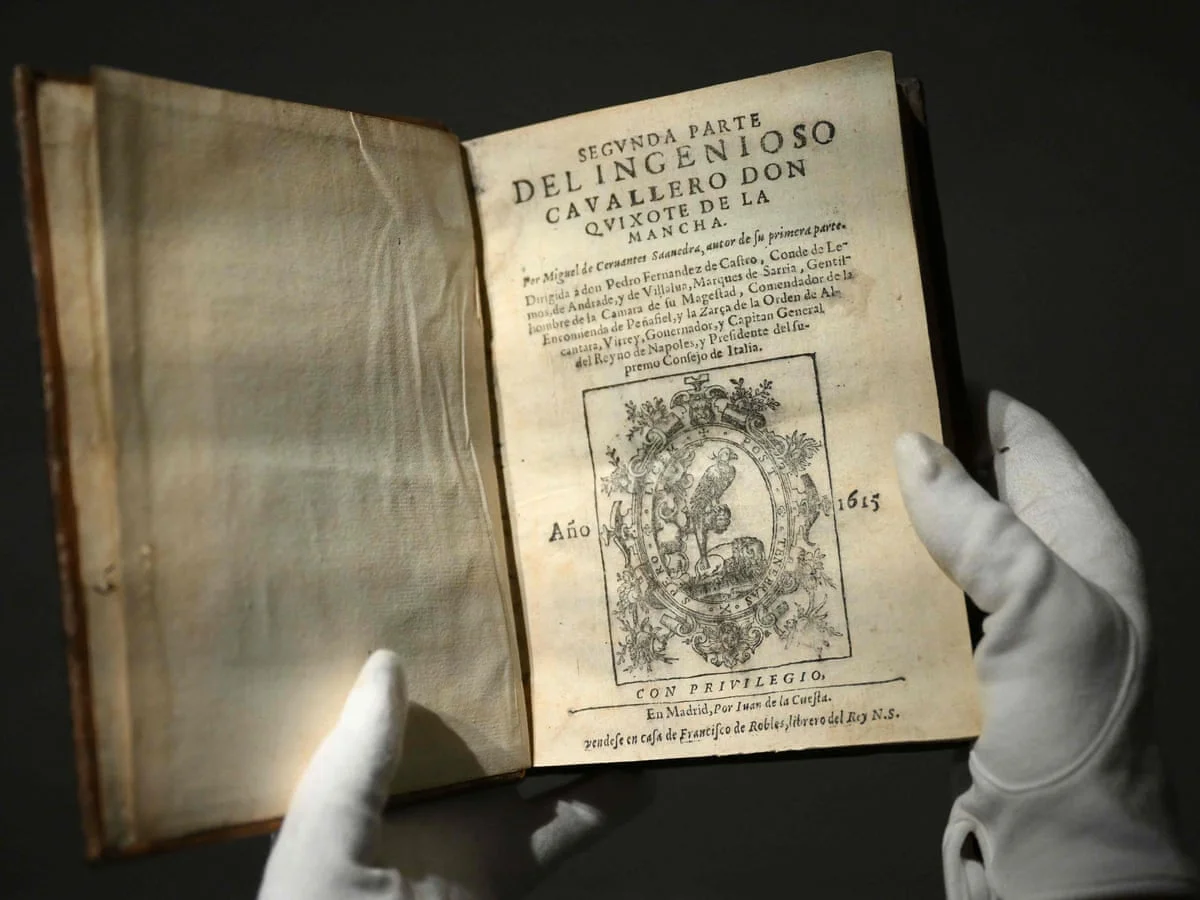

Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote, first published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, is often hailed as the first modern novel and one of the most influential works of world literature. Its satirical brilliance, layered narrative, and philosophical depth have inspired countless writers, artists, and thinkers for centuries.

Yet, when it comes to cinema, Cervantes’s masterpiece has proven notoriously difficult to adapt. Filmmakers from Orson Welles to Terry Gilliam have struggled, often for decades, to bring the knight of La Mancha convincingly to the screen. The challenge lies not simply in its historical setting but in the novel’s unique blend of parody, metafiction, and psychological subtlety, which resists the linear storytelling conventions of film.

The novel’s complex structure

One of the primary obstacles in adapting Don Quixote is its sprawling and episodic structure. The book follows the deluded knight and his squire, Sancho Panza, across Spain in a series of loosely connected adventures. Unlike novels with a central plot that builds toward resolution, Don Quixote is fragmented, digressive, and deliberately inconsistent. Cervantes constantly shifts tone between comedy, tragedy, and philosophical reflection. A film adaptation, constrained by time and narrative coherence, struggles to capture this shifting rhythm without either oversimplifying or overwhelming viewers with episodic chaos.

The metafictional layers

Cervantes pioneered metafiction long before the term existed. The novel pretends to be a historical chronicle written by a Moorish author, Cide Hamete Benengeli, with Cervantes acting as a mere translator. Later, the characters themselves become aware of their own fame within the fictional world after the publication of the first part of the book. This self-referential playfulness destabilizes the boundary between fiction and reality. Cinema, which tends to rely on immersive illusion, struggles to convey this without confusing audiences or reducing the device to a gimmick. Few films have managed to capture the novel’s intricate dance between storytelling and self-awareness.

The challenge of Don Quixote’s character

Don Quixote himself is a paradoxical figure—ridiculous yet noble, deluded yet insightful, tragic yet comic. He is not merely a caricature of a foolish old man tilting at windmills, but a richly layered character whose idealism reveals deeper truths about human longing and dignity. Translating this complexity onto the screen requires extraordinary balance: too much emphasis on comedy reduces him to a buffoon, while too much gravity makes him into a lifeless symbol. Striking the right tonal register has proven elusive, with many adaptations leaning heavily toward satire at the expense of pathos or vice versa.

Sancho Panza’s transformation

Sancho Panza, Don Quixote’s squire, presents another difficulty. He begins as a simple, self-serving peasant but gradually transforms into a voice of wisdom and loyalty. His dynamic relationship with Quixote is at the heart of the novel. However, film adaptations often flatten Sancho into a comic sidekick, missing the nuance of his evolving perspective. Capturing the subtle interplay of power, friendship, and mutual influence between knight and squire demands more screen time and narrative care than most films can afford.

The novel’s philosophical depth

Beyond its plot, Don Quixote is a meditation on reality, illusion, and the human desire for meaning. The knight’s insistence on seeing windmills as giants or inns as castles is more than delusion; it is a profound commentary on the power of imagination to shape human experience. Film adaptations tend to reduce these moments to comedic absurdity, losing the existential weight Cervantes infused into them. Conveying such philosophical themes visually without lengthy dialogue or narration requires exceptional cinematic invention, which few directors have achieved.

The vast cultural and historical context

Cervantes wrote at a time when Spain was experiencing cultural upheaval, with declining imperial power and shifting social structures. Don Quixote reflects this context through its parody of chivalric romances, commentary on social hierarchies, and satire of outdated ideals. Modern audiences, however, are far removed from the world of sixteenth-century Spain. Filmmakers must either invest time in contextual explanation—which risks slowing the narrative—or strip away historical layers, reducing the story to universal themes but losing its cultural richness. Striking a balance between accessibility and fidelity is no small feat.

The weight of expectations

Another reason why adapting Don Quixote is so daunting lies in its status as a canonical masterpiece. Every filmmaker attempting the task must wrestle with centuries of interpretation and expectation. Audiences and critics alike approach any adaptation with skepticism, judging it not only as a film but as a statement about one of literature’s greatest works. This burden has led to famously troubled productions. Orson Welles worked on his version for decades but never completed it. Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote faced production disasters for nearly thirty years before a film finally emerged, by which time expectations had become nearly impossible to meet.

Visualizing the unfilmable

The novel’s most iconic scenes—Don Quixote attacking windmills, mistaking sheep for armies, or wearing a barber’s basin as a helmet—have become cultural shorthand for delusion. Yet these moments risk becoming clichés when translated literally to film. The true power of these episodes lies not in their visual spectacle but in the way Cervantes narrates them, blending irony, compassion, and philosophical insight. A straightforward cinematic depiction often falls flat because it cannot reproduce the narrative voice that gives them depth.

Why partial adaptations succeed more than full ones

Interestingly, some of the most successful attempts to bring Don Quixote to the screen have been partial or indirect. Films that borrow themes or reimagine the story in new contexts—such as Man of La Mancha, the musical, or Gilliam’s reinterpretation—often fare better than those attempting literal adaptation. By focusing on the spirit rather than the letter of the novel, they capture Quixote’s enduring relevance as a symbol of impossible dreams and stubborn idealism. This suggests that true fidelity to Cervantes may lie not in replicating his book scene for scene but in channeling its essence into new artistic forms.

The impossible quest continues

Adapting Don Quixote to film is itself a quixotic endeavor—a noble but nearly impossible quest. The novel’s digressive structure, metafictional layers, philosophical richness, and cultural specificity resist cinematic conventions. Yet the continued attempts testify to the story’s enduring power to inspire imagination and artistic ambition. Much like Don Quixote himself, filmmakers who pursue this task are driven by ideals that may be unattainable but are nonetheless worth striving for. In this way, every failed or flawed adaptation becomes part of the novel’s legacy, proving that some works are not meant to be captured but continually reimagined.