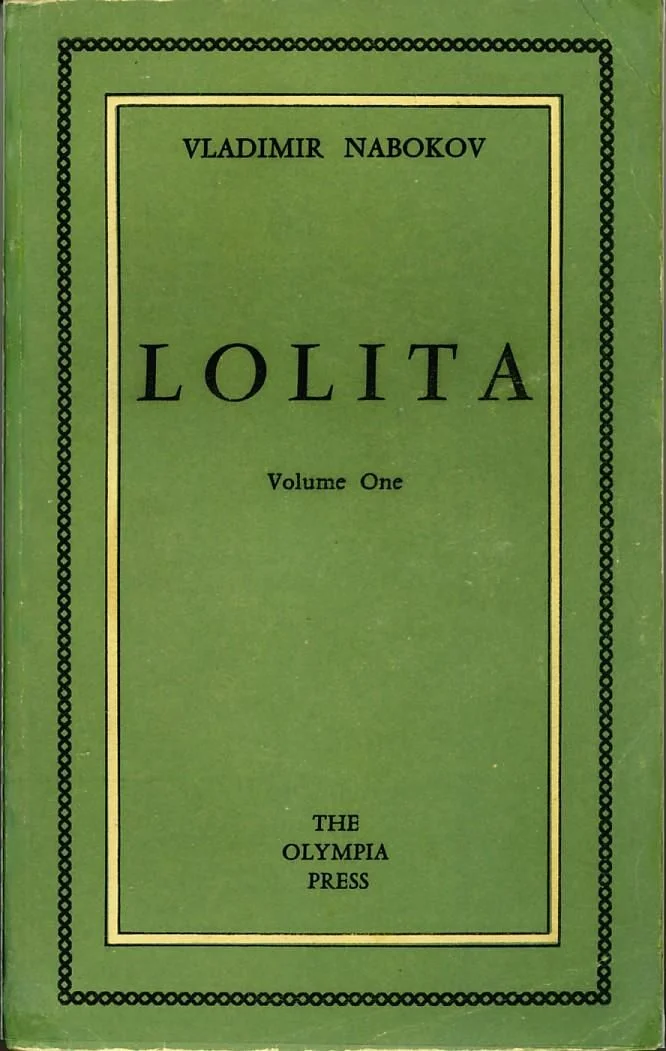

Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel Lolita has long been recognized as one of the most controversial works of modern literature. Its story of Humbert Humbert’s obsession with a twelve-year-old girl sparked outrage, fascination, and debate from the moment of publication.

When filmmakers attempted to bring Lolita to the screen, they faced immense challenges: how to translate a narrative filled with disturbing subject matter into a cinematic form without violating censorship laws, alienating audiences, or betraying Nabokov’s artistry. The adaptations of Lolita, particularly Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film and Adrian Lyne’s 1997 version, reveal much about how cinema has navigated themes of taboo desire, morality, and representation.

The challenge of adapting Nabokov’s prose

Nabokov’s novel is often considered unfilmable not because of its subject matter alone but because of its style. Much of the book’s impact lies in its language—Humbert’s unreliable narration, lyrical descriptions, and dark humor. Readers are drawn into complicity by Humbert’s eloquence, even as the narrative exposes his manipulation and cruelty. Cinema, however, relies on images rather than internal monologues. Filmmakers faced the difficulty of preserving the novel’s tension between Humbert’s seductive voice and the horror of his actions. This challenge shaped the direction of both major film adaptations.

Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation

Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita, released in 1962, was made during a time of strict censorship under the Hollywood Production Code. Direct depictions of Humbert’s sexual obsession with a minor were impossible. Kubrick and screenwriter Nabokov himself, who drafted a screenplay that was later heavily cut, had to find indirect methods to suggest the novel’s themes without showing them explicitly. The result was a film that downplayed the disturbing aspects of Humbert’s relationship with Lolita and emphasized satire, irony, and dark comedy instead.

Changes to character dynamics

In Kubrick’s version, Lolita is portrayed by Sue Lyon, who was fifteen during filming but made up to appear older. This casting choice softened the shock of Humbert’s obsession by presenting Lolita as more mature than Nabokov’s twelve-year-old character. By making her appear closer to adolescence, Kubrick navigated censorship rules but also altered the dynamic of the relationship. What was predatory and grotesque in the novel became, on screen, a controversial but less overtly criminal romance. The film’s Lolita has agency and flirtatiousness, shifting audience perception in ways Nabokov never intended.

Use of humor and satire

Kubrick leaned heavily on humor to navigate the taboo subject. Scenes with Clare Quilty, played by Peter Sellers, provided absurd comedy that distracted from the darker elements of Humbert’s actions. This tonal shift allowed the film to pass censorship but also diluted the novel’s disturbing critique of manipulation and abuse. While Kubrick’s film became a landmark in its own right, it left many critics divided on whether it captured Nabokov’s moral ambiguity or sidestepped it entirely.

Lyne’s 1997 adaptation

By the time Adrian Lyne released his adaptation in 1997, censorship standards had shifted, allowing for a more direct treatment of the subject matter. Starring Jeremy Irons as Humbert and Dominique Swain as Lolita, the film sought to restore some of the novel’s unsettling qualities. Unlike Kubrick’s satirical tone, Lyne emphasized melodrama and emotional intimacy, portraying Humbert as both predatory and tormented. The film attempted to capture Nabokov’s blend of horror and lyricism through more explicit depictions of Humbert’s obsession.

Controversies surrounding Lyne’s version

Despite aiming for greater fidelity, Lyne’s adaptation faced significant controversy. The depiction of Lolita as a vulnerable yet sexualized teenager raised ethical questions about representation and exploitation. Critics argued that the film risked replicating Humbert’s gaze by eroticizing the character, even as it sought to critique him. Distribution challenges followed, with some countries restricting screenings. The controversy demonstrated that even decades later, Lolita remained one of the most difficult novels to adapt faithfully without igniting public backlash.

Faithfulness versus interpretation

Both Kubrick and Lyne approached Lolita with different strategies, yet both diverged from Nabokov’s original vision in significant ways. Kubrick avoided explicitness through satire and casting choices, while Lyne leaned into emotional drama and darker realism. Neither fully captured Nabokov’s narrative voice—the unreliable, ironic prose that makes readers complicit. This gap highlights a broader challenge in literary adaptations: how to translate not just plot but narrative technique. In the case of Lolita, the prose is inseparable from the story’s impact, and cinema struggles to replicate that.

The role of censorship and audience sensitivity

The history of Lolita’s adaptations also reflects broader cultural shifts in how societies confront taboo themes. In the 1960s, censorship demanded evasion and subtext. By the 1990s, greater openness allowed for explicitness but also triggered debates about ethics and representation. The adaptations reveal how cinema not only interprets literature but also reflects the cultural climate in which it is produced. Each version of Lolita is as much a commentary on its time as it is on Nabokov’s novel.

Lessons from adaptation history

The attempts to bring Lolita to the screen highlight the limitations of cinema when confronting morally complex literature. Nabokov’s novel forces readers into discomfort by combining beauty of language with horror of content. Films, bound by visual representation, cannot sustain that same tension without risk of exploitation or misinterpretation. As a result, adaptations inevitably soften, alter, or distort the original work. Yet these efforts also demonstrate cinema’s capacity to provoke discussion, ensuring that Lolita remains relevant in debates about art, ethics, and storytelling.

Cinema’s uneasy mirror

Ultimately, the adaptations of Lolita illustrate cinema’s uneasy relationship with controversial literature. Neither Kubrick’s satire nor Lyne’s melodrama fully resolved the challenges of portraying Humbert and Lolita’s story, but both revealed how films navigate censorship, audience expectation, and artistic ambition. These adaptations function less as faithful translations of Nabokov’s prose than as cultural mirrors, reflecting the anxieties and boundaries of their eras. In this sense, the history of Lolita on screen is itself a study of how art contends with the most difficult questions of morality and representation.