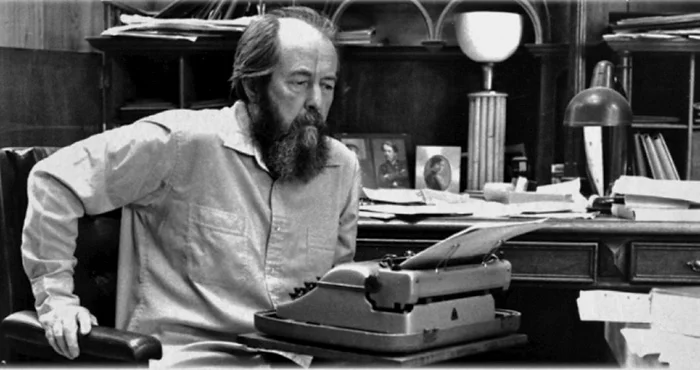

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn stands as one of the most influential literary figures of the 20th century—a man whose personal journey through persecution, imprisonment, and exile became inseparable from his literary voice.

His powerful critiques of totalitarianism, particularly that of the Soviet Union, earned him both the Nobel Prize in Literature and the animosity of the state he once served. Yet it was political exile, both internal and external, that shaped the evolution of his philosophy and profoundly impacted the themes, tone, and structure of his work.

More than a biographical detail, exile was a crucible in which Solzhenitsyn’s ideas about freedom, responsibility, and moral courage were tested and clarified. His enforced separation from his homeland pushed him into deeper engagement with the Russian identity, the nature of tyranny, and the role of the writer in society.

Exile as a Continuation of Imprisonment

To understand Solzhenitsyn’s exile, one must first consider the context of his early life. Arrested in 1945 for criticizing Stalin in private letters, Solzhenitsyn spent eight years in Soviet labor camps and three more in internal exile. These experiences were foundational to his writing, particularly in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and The Gulag Archipelago. They provided not just raw material, but a profound psychological perspective on human endurance, institutional cruelty, and spiritual survival.

While release from prison brought nominal freedom, the reality for Solzhenitsyn was more complicated. Though he gained recognition in the early 1960s when his first major work was published with official approval, his relationship with the Soviet state rapidly deteriorated as his writing became more openly critical. Censorship returned, and his manuscripts were smuggled abroad. In 1974, after years of harassment and surveillance, he was arrested again—not for his actions, but for his words—and forcibly expelled from the Soviet Union.

Thus began a different kind of imprisonment: a life in political exile, cut off from his homeland, living in the West as both celebrity and outsider.

The West: Freedom with Ambivalence

Solzhenitsyn’s arrival in the West, particularly his time in Switzerland and later in Vermont, offered him a level of personal freedom unimaginable in the USSR. He could write without fear of censorship, speak publicly, and correspond freely with supporters. Yet this newfound liberty brought its own set of conflicts.

Far from embracing the West as a haven of ideal democracy, Solzhenitsyn became a vocal critic of Western materialism, secularism, and moral relativism. In his famous 1978 Harvard Commencement Address, “A World Split Apart,” he condemned not just the tyranny of communist regimes but also the spiritual emptiness he perceived in liberal democracies.

This position placed him in a complex space: admired for his courage but often criticized for his worldview. Some saw him as a prophet; others as a moral absolutist out of step with modernity. Still, exile allowed Solzhenitsyn to explore what he saw as a deeper crisis of civilization—one not limited to any single political system.

This phase of his exile produced a more global critique, expanding beyond the Soviet Union to explore universal themes of conscience, historical memory, and the role of moral responsibility in public life.

The Writer in Exile: A Shift in Literary Vision

The transformation Solzhenitsyn underwent in exile was not merely personal or political—it was literary. In the USSR, his work had been shaped by necessity and survival: short forms, compressed narratives, allegorical strategies. Outside the constraints of censorship, his writing became more expansive, ambitious, and historically sweeping.

This is most evident in The Red Wheel, his multi-volume epic about the lead-up to the Russian Revolution. Written largely during his exile in Vermont, this work reflected his desire to reconnect with Russian history on his own terms. He delved into the moral failures and social ruptures that, in his view, paved the way for Bolshevik tyranny.

Exile gave Solzhenitsyn the space and time to pursue such massive undertakings. But it also highlighted a key theme in his evolving work: the idea that true history must be preserved and re-examined by those willing to confront uncomfortable truths. Without exile, this literary excavation might never have occurred at such a scale.

Identity and Longing: Russia from Afar

Though physically distant from Russia, Solzhenitsyn remained intellectually and emotionally anchored to it. His works continued to wrestle with questions of Russian identity, national character, and the burden of history. Exile sharpened his sense of what he saw as the moral and spiritual duty of the Russian people.

He did not idealize his homeland—on the contrary, he condemned many aspects of Soviet society. But he did insist that Russian culture contained within it the seeds of renewal, provided it could reconnect with its ethical and spiritual roots. This belief informed his public statements and essays throughout his exile and framed his eventual return to Russia in 1994 not as a homecoming to a state, but to a people and a legacy.

In many ways, exile deepened his Russianness. Separated from the geography of his youth, he found in language, history, and faith a portable form of national identity. His writing became a vessel for cultural memory—a way to carry Russia with him, even when politically severed from its soil.

Exile as a Moral Platform

One of the most important consequences of Solzhenitsyn’s exile was the platform it gave him to speak to the world. While inside the Soviet Union, he had limited means to disseminate his views. In the West, he became a symbolic figure—an emblem of dissent, courage, and unflinching moral witness.

But Solzhenitsyn used this platform not for self-promotion, but to confront difficult truths. He criticized both Soviet totalitarianism and Western complacency. He challenged writers, intellectuals, and political leaders to recognize their moral responsibility not just to freedom of speech, but to truth-telling, historical reckoning, and spiritual renewal.

Exile, then, became more than a condition—it became a role. Solzhenitsyn positioned himself as an exiled conscience, someone whose outsider status gave him the clarity to speak without allegiance to party, nation, or ideology.

Return Without Illusion

When Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia in the mid-1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union, it was not as a triumphant hero, but as a reflective observer. He remained critical of the new government’s direction, particularly its embrace of capitalism without moral reform. He declined to re-enter political life, choosing instead to continue his literary and philosophical work.

This final chapter of his life suggests that exile had permanently altered him. He no longer saw Russia as a place to be reclaimed in political terms, but as a moral and cultural project still in need of healing. His return was not about personal vindication—it was about the continuation of a lifelong commitment to truth, no matter how uncomfortable.

Exile as Creative and Moral Catalyst

For Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, political exile was not a detour from his life’s mission—it was the fire through which that mission was refined. Removed from his homeland, he found his clearest voice. Denied access to the institutions of power, he spoke with greater moral force. Separated from the familiar, he saw the universal.

In exile, Solzhenitsyn did not lose his identity; he expanded it. He became not just a Russian dissident, but a global thinker whose reflections on truth, power, and human dignity continue to resonate. His life reminds us that exile, while a form of suffering, can also be a path to deeper understanding—and to the kind of clarity that only distance can provide.