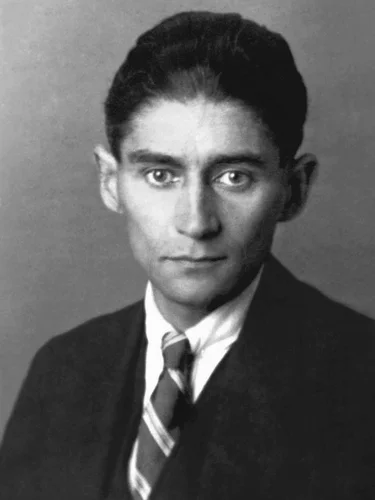

Franz Kafka, one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, left behind a body of work that reshaped modern literature. Yet much of this work—novels, short stories, notebooks, and personal reflections—was never intended to be published.

In fact, Kafka explicitly asked his close friend and literary executor Max Brod to destroy his unpublished writings after his death. That wish, as we know, was never honored. Brod instead chose to preserve and publish the manuscripts, introducing Kafka’s visionary fiction to the world.

Why would a writer as singular and insightful as Kafka choose to hide so much of his work from public view? The answer lies not in a single explanation, but in a tangle of personal, psychological, and philosophical factors.

Kafka’s self-doubt, his conflicted relationship with writing, and his views on authorship and identity all contributed to this decision. Understanding why he concealed his manuscripts offers us not only insight into Kafka’s mind, but also into broader questions about the nature of art, privacy, and legacy.

A Life of Reluctant Authorship

Kafka’s writing life was marked by ambivalence. While he wrote prolifically—from late-night sessions to scribbled notes during work hours—he published very little during his lifetime. His major novels (The Trial, The Castle, Amerika) remained incomplete and unpublished at the time of his death in 1924. Even many of his shorter works, such as “The Hunger Artist” and “In the Penal Colony,” were published only after significant hesitation and revision.

Kafka often viewed his literary output as inadequate. He once confessed in a letter to Max Brod that “everything I leave behind me is to be burned unread.” This wasn’t a performative gesture—it was a deeply held belief. Despite his critical insight and intellectual brilliance, Kafka considered himself a failure as a writer. The manuscripts he left behind were not simply unfinished; to him, they were unworthy.

Perfectionism and Creative Torment

One major reason Kafka hid his work was perfectionism. He was notoriously self-critical, often revisiting, revising, and ultimately abandoning manuscripts he deemed unsatisfactory. Unlike writers who accepted the idea of draft and refinement as part of the process, Kafka seemed paralyzed by the gap between what he envisioned and what he could express.

He saw his work not as personal triumph, but as a constant struggle against the limitations of language. In his diaries, he described writing as a form of torment—necessary but painful. This inner conflict led him to believe that his works, especially those left incomplete, should not survive him. They didn’t meet his standards; they didn’t communicate the depth he felt or feared.

This perfectionism was intensified by Kafka’s hypersensitivity to judgment—both his own and that of others. He feared being misunderstood. Perhaps he believed that readers, unable to grasp the emotional or metaphysical nuances of his work, would flatten his ideas or misinterpret his themes.

The Influence of Illness and Mortality

Kafka’s declining health also played a role in his decision to conceal or destroy his work. He suffered from tuberculosis, which progressed steadily over the last years of his life. As his body weakened, his sense of urgency sharpened, but so did his disillusionment. He may have felt that his time was ending, and with it, his chance to “fix” or complete his literary projects.

In this context, his instruction to Brod can be seen as an effort to assert control over his legacy. Dying, Kafka had no interest in curating his public image or capitalizing on posthumous fame. Rather than leave a fractured or partial impression of himself through unfinished manuscripts, he preferred silence. His act of concealment was not only about hiding imperfection—it was about maintaining integrity in the face of mortality.

Identity, Anonymity, and the Role of the Writer

Kafka also had a complex view of authorship. He distrusted fame and was wary of the cult of personality surrounding writers. In his letters and diaries, he often expressed discomfort with the idea of the author as a public figure. He once wrote, “Writing is a form of prayer.” For Kafka, writing was a sacred, private act—an attempt to understand the self, not a means of gaining recognition.

By hiding his manuscripts, Kafka preserved that intimacy. He separated the act of creation from the act of publication. Unlike many writers of his era who embraced public platforms or political visibility, Kafka retreated. His desire for literary anonymity echoed his personal shyness and detachment from society. Writing, for him, was internal and introspective—not a performance, but an excavation.

The Role of Max Brod: Betrayal or Salvation?

Kafka’s friend and confidant Max Brod plays a crucial role in the story. Despite Kafka’s clear instructions, Brod chose to preserve and publish the manuscripts. Was this an act of betrayal, or of literary duty? Brod justified his decision by arguing that Kafka’s work was too important to destroy. He believed Kafka wrote with the silent hope that someone would override his request—that Kafka wanted to be read, even if he couldn’t admit it.

Brod’s decision has sparked ongoing ethical debate. Some argue that honoring Kafka’s wishes would have meant sacrificing some of the most important literature of the modern age. Others insist that an artist’s instructions—especially regarding unpublished work—should be respected. Yet Brod’s choice also reminds us that literary legacy is rarely something a writer controls. It is shaped as much by relationships and readers as by the author’s own intent.

What Kafka’s Hidden Manuscripts Reveal

Ironically, the very manuscripts Kafka tried to hide reveal the depth and brilliance he denied himself. They show a writer grappling not just with narrative or plot, but with existence, guilt, alienation, bureaucracy, and metaphysical anxiety. They offer fragments of truth in the raw, capturing the intellectual restlessness that defined Kafka’s worldview.

Moreover, Kafka’s concealment of his work now forms part of his mythos. His reluctance became a statement in itself—about art, privacy, and the burden of being seen. His hidden manuscripts challenge modern assumptions about creativity and visibility. They force us to consider whether the value of art lies in its exposure, or in its authenticity.

Silence as Legacy

Franz Kafka’s decision to hide so many of his manuscripts was not simply a matter of insecurity or eccentricity. It was a profound expression of his inner conflict as a writer—between the desire to express and the fear of exposure, between the sacredness of writing and the noise of public life. By instructing Brod to destroy his work, Kafka tried to control the boundary between his inner world and the outside gaze.

Yet history unfolded differently. And perhaps, in the contradiction between Kafka’s wishes and Brod’s defiance, we see the essence of Kafka’s literature: that human intention is always entangled in forces beyond control, and that meaning is found not in resolution, but in the tension itself.